Tapping Ink, Tattooing Identities Tradition and Modernity in Contemporary Kalinga Society North Luzon, Philippines

“Tapping Ink, Tattooing Identities is a unique account of contemporary and past tattooing practices among the Kalinga people in northern Luzon. Based on long-term and in-depth fieldwork, the author documents traditional tattooing practices and designs and explores the origins and meanings of designs. However, this book also takes into account the contemporary relevance of tattooing as an aspect of asserting identity as well as a practice that draws tourists into the region. As such, the author demonstrates comprehensively that the tattooing practices of the Kalinga have both a long history as well as a hopefully vibrant future.

Salvador-Amores’ fieldwork and analysis builds sensitively on the strong social relations she managed to built up in the course of her research most notably with the extraordinary tattooing expert Whang-ud whose own life story is woven through the book.”

—Elizabeth Ewart and Marcus Banks, Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Oxford

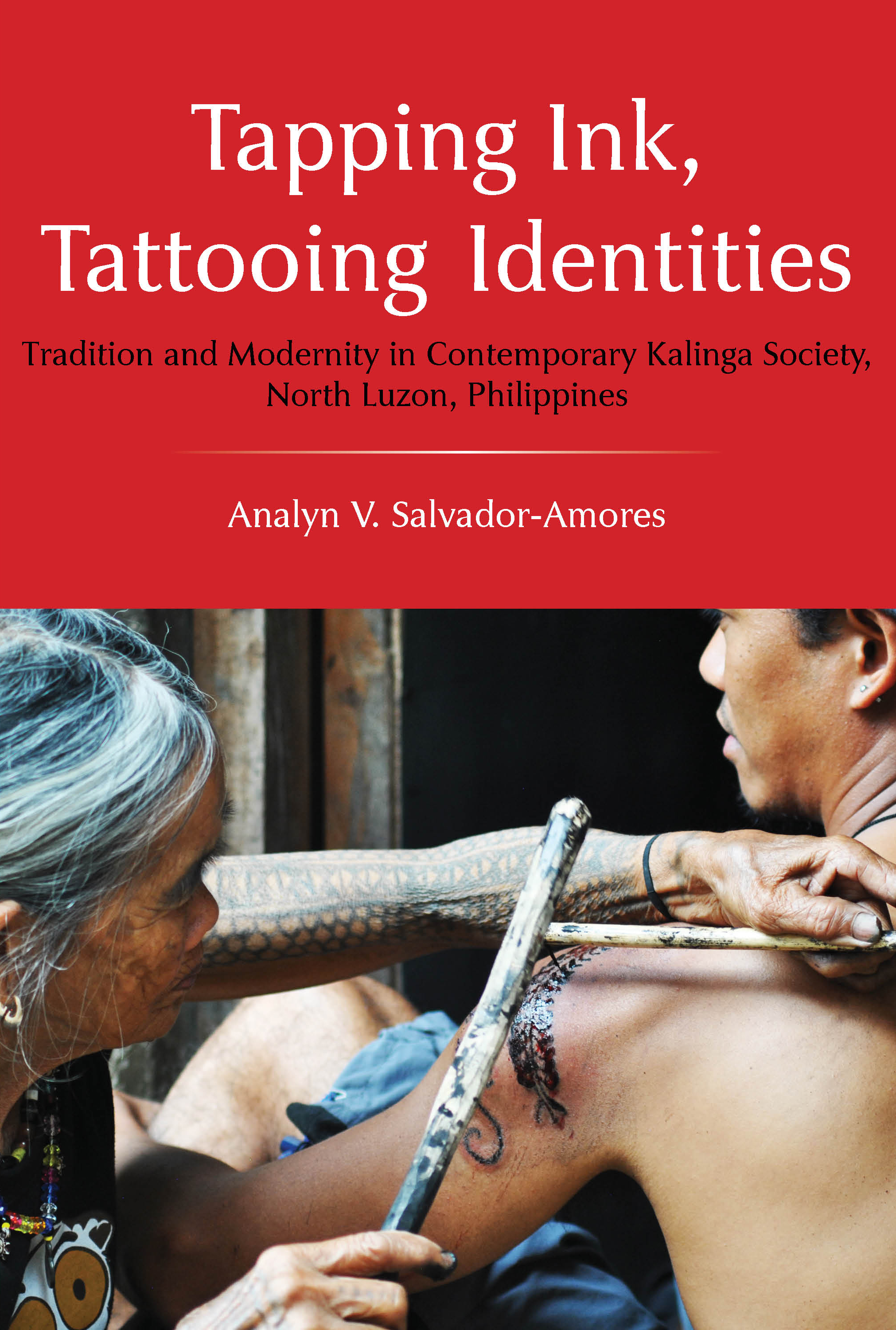

Written in profound narrative, and ethnographic style, Tapping Ink, Tattooing Identities revolves around Whang-ud—her life, her approach to tattooing, and her activity as a tattoo practitioner—the ethnography, however, extrapolates an analysis of Kalinga tattooing from this one central character. Whang-ud, the ninety-year-old tattoo practitioner, is the living embodiment of the transition between traditional and modern tattooing.

While in recent decades, there has been a significant decline in traditional tattooing practices in the Cordillera region, North Luzon, Philippines, specifically among the Butbut, in one remote southern Kalinga village, there has been an unprecedented revival. This revival has been spurred largely by urban Filipinos, diasporic Filipinos, and non-Kalinga people (e.g., local and foreign tourists) who travel to Buscalan to get tattooed by Whang-ud. Diasporic Filipinos of non-Kalinga origins, as well as urban Filipinos and young Butbut-Kalinga themselves, are turning to Kalinga tattoos as an expression of cultural authenticity and identity. Notions of “tradition,” “modern,” “authenticity,” and “revived” are problematized in the Butbut tattooing context, together with the argument that tattoos, once markers of collective identity have now more to do with the identity of the individual. The continuity of tradition is based on engagement with modernity incorporated into the Butbut way of life as a new form of sociality, as part of the many “traditions” or “alternatives” of being modern.

About the Author:

Analyn “Ikin” Salvador-Amores was born and raised in Baguio City to Ilocano parents. As a child, she remembers selling garlic and onions in her Lola Gorings’s stalls at the old Baguio Public Market. She recalls her fascination with the tattooed old women who sold their produce at the market. Years later, as an aspiring graduate student of Anthropology at the University of the Philippines, her interest in traditional tattoos was once again piqued when she met an old Bontoc woman selling red mountain rice. This chance encounter inspired her to conduct research and document traditional tattoos and other body adornments in Kalinga and other parts of the Cordillera. It is curiosity and the need to know that encourages Ikin to conduct an in-depth research. Much of her interest begins with a genuine interest in people and their cultures.

In 2006, Ikin was selected as an International Fellow of the Ford Foundation that enabled her to pursue graduate studies in the UK. Ikin entered the MPhil (Master of Philosophy) in Social Anthropology in the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography at the University of Oxford and wrote on tattoos in colonial photographs of the Igorots for her thesis. After earning her MPhil in 2008, she pursued her doctorate (DPhil) in Social and Cultural Anthropology at the same institution. This time, she wrote about what was closest to her heart, studying Kalinga’s traditional tattoos as markers of identity from the indigenous to diasporic in contemporary Kalinga society. This book, her first, is her dissertation.

After Oxford, Ikin resumed teaching at the College of Social Sciences, University of the Philippines in Baguio. She continues to publish and do research in the Cordilleras. Among her interests are anthropology of the body, non-Western aesthetics, material culture, visual anthropology, museum studies, and anthropology of development.